Why is Bush so obsessed with ungrateful foreigners?

Posted Tuesday, March 13, 2007, at 4:59 PM ET

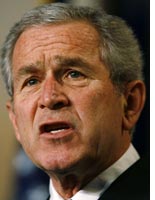

George W. Bush

George W. Bush

What is it with George W. Bush and his insistent demand for the gratitude of foreigners?

In São Paulo, Brazil, last week, on the first day of his Latin America tour, the president said, "I don't think America gets enough credit for trying to improve people's lives." BAH!

The complaint was reminiscent of earlier expressions of pique.

In his memoir of his year in Baghdad as head of the Coalition Provisional Authority, L. Paul Bremer recalled that President Bush once told him that the leader of a new Iraqi government had to be "someone who's willing to stand up and thank the American people for their sacrifice in liberating Iraq."

Bremer noted that Bush made this point three times in the course of a single conversation and further insisted that the president of Iraq's first interim government should be Ghazi al-Yawar, an obscure Sunni Arab businessman, because Bush "had been favorably impressed with his open thanks to the Coalition."

It was no coincidence, therefore, that when Iyad Allawi, Iraq's first American-handpicked prime minister, held his maiden press conference in June 2004, he broke into English to say, "I would like to thank the coalition, led by the United States, for the sacrifices they have provided in the … liberation of Iraq."

President Bush, at his own press conference soon afterward, drew attention at least twice to Allawi's gratitude.

In September 2004, when Allawi traveled to Washington to speak before a joint session of Congress, one of his opening lines (recited from a speech written mainly by the White House) was: "We Iraqis are grateful to you, America, for your leadership and your sacrifice for our liberation and our opportunity to start anew."

Just this past January, in an interview with CBS's 60 Minutes, President Bush returned to the theme, this time annoyed that the people he'd liberated seemed so unappreciative.

"I think the Iraqi people owe the American people a huge debt of gratitude," he said. "I mean … we've endured great sacrifices to help them," and the American people "wonder whether or not there is a gratitude level that's significant enough in Iraq."

There's a skewed view of the world reflected in these remarks. Does Bush really fail to recognize that even the most pro-Western Iraqis might have mixed feelings, to say the least, about America's intervention in their affairs—that they might be, at once, thankful for the toppling of Saddam Hussein, resentful about the prolonged occupation, and full of hatred toward us for the violent chaos that we unleashed without a hint of a plan for restoring order?

Bush may have had a political motive in making these remarks. He may have calculated that Americans would be more likely to support the war if the people for whom we're fighting thanked us publicly for the effort. By the same token, their palpable lack of gratitude, and the war's deepening unpopularity at home, might have heightened his frustration and impelled such peevish outbursts.

But this peevish imperiousness is precisely what's most disturbing about Bush's incessant concern with the proper level of fealty.

The word that he repeatedly uses when discussing what he wants from nations he thinks he's helping—"gratitude"—implies a supplicant's relationship to his lord.